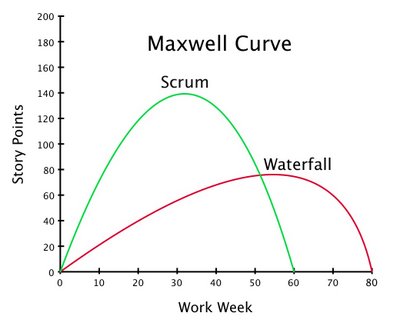

Scott Downey, MySpace Agile Coach, has a way of bootstrapping Scrum teams to a high performing state in a company that is about 1/3 waterfall, 1/3 ScrumButt with project managers, and 1/3 pure Scrum with only Scrum roles. Scott consistently takes teams to 240% of the velocity of MySpace waterfall teams in an average of 2.9 days per team member where the team includes the ScrumMaster and Product Owner.

At OpenView Venture Partners, we see portfolio companies with aggressive implementation of Scrum triple velocity in three Sprints (usually 2 week Sprints). Scott uses one week Sprints and it takes him about three Sprints.

I heard similar stories from an Agile leader at JayWay in Sweden. Using a forceful and mandatory way of implementing Scrum and good engineering practices, that Agile leader got similar results to MySpace.

Rob Mee at Pivotal Labs in San Francisco uses a forceful total XP immersion experience to bootstrap teams. They do everything exactly his way for three months. After that they have full body understanding of the Agile motion and he can send them on their way. It has worked well on 40 startups so far.

It may be that great Scrum teams need to go to boot camp or give themselves Shock Therapy in the same way a student of the martial arts gets thrown for a loop the first night on the mat and it never lets up until he masters the practice with his body as well as the mind.

I encouraged Scott Downey at MySpace to share his strategy with Björn Granvik, the CTO of JayWay in Sweden, and he wrote the details below. I'll be sharing this at Google in New York tonight along with thoughts on the Cosmic Stopping Problem and Punctuated Equilibrium and how they relate to the effects seen by Scott. For that, you will have to wait for the Google video.

--------

Hi Björn,

I'm sorry to say that I don't have anything formally written as yet, but I am working on it! I'm in the process of being a full time employee for MySpace while consulting for a few other companies on jump-starting their Scrum so my quiet time for writing is a bit rare these days. I'm happy, though, to describe roughly what I do that makes me the "hated" character Jeff described for the first 2-3 weeks. :-)

Scrum, as a framework, provides teams a ton of options for how to customize it to their own environment. In my experience, most teams just starting out are so overwhelmed with choices that they can't find a constructive way to start. I have known of teams that spent so much time designing their Scrum Board, for example, that Management lost patience with them and the Scrum process because a Scrum Board was all they ever produced.

It occurred to me one day that Scrum Teams are the customers of the Scrum Master. We all know that customers of our enterprise don't really know what they want until they have seen it. So why do we expect Scrum Teams to know how to set up their Planning Meetings if they haven't seen a prototype? So when I join a team as their Scrum Master, I issue a few non-negotiable rules (gently if possible, firmly if necessary). My rules remain in effect until the team has met three criteria:

- They are Hyper-Productive (>240% higher targeted value contribution)

- They have completed three successful Sprints consecutively

- They have identified a good business reason to change the rule

The rules are roughly these:

- Everyone on the team will attend a Scrum Training session.

I conduct an extremely condensed Scrum at MySpace course in about four hours, and the entire team comes together to a session. Until everyone has been trained, we won't begin our first Sprint.

- Sprints will be one week long.

I justify this by pointing out that there is a reason geneticists study mutations in Fruit Flies instead of Elephants – they want to see the mutations quickly and adapt their studies accordingly. So do I. Teams generally hate this part as much or more than anything else I require of them but I have been able to coax every team into giving me at least four, one-week Sprints as a trial. Here's a favorite exchange of mine that almost always comes up – feel free to use it:

Engineer: "But I can't do anything in a week!"

Scott: "Then simple math suggests that you can only do four nothings in a month."

Interestingly, by the time the teams have met the three criteria for changing this rule, only one so far has ever elected to change it.

- They will start out by using my definition of "Done".

This is often one of the thorniest issues to iron out with a team, so I take it off the table until they have some shared success as a foundation. My initial definition of "Done" is this: - Feature Complete

- Code Complete

- No known defects

- Approved by the Product Owner

- Production Ready

- All estimates will be exclusively in Story Points.

Again, this one is sometimes met with a ceremonial rolling of the eyes but – so far, anyway – they have all eventually come around to this. It's usually at about week three when I can intentionally spark a debate over whether a card is a 3 or a 5, then have the pleasure of pointing out to them the passion with which they are debating these recently-meaningless values. I also make a point of shouting "BA!" whenever they all vote the same value for a given card. My intent is to show them how often they actually agree in their vote. As the mood on the team lightens up, some teams begin scanning the other votes and "baa"ing like sheep when that happens. Only one has returned my "Ba!" with a "Humbug!" In any event, they all start having fun with it and that's important.

- We will use a physical Information Radiator.

Not only do I insist on a physical Information Radiator, but I have a basic template that I use initially for all teams. I choose the location of the Scrum Board unilaterally and use it as the focus of the Daily Stand-Up Meeting. When the team is first formed, I let them focus on the interaction with their teammates (the three Achievement questions ) and I move their cards across the Radiator's surface myself. Within a couple of weeks, they start moving cards themselves without having been asked. This is usually my first indication that I can begin slowly stepping back and relaxing my demands.

- Sprint Planning Meetings will be four hours, once per week.

The first complaint of most Engineers is that they perceive Scrum imposing a highly disruptive schedule on them, with more meetings than they somehow think they have ever had before. To minimize this common concern, I consolidate everything but the Daily Stand-Up meetings into a single, four-hour meeting. Within a few weeks, the teams usually only needs a couple of hours. And by the end of about eight Sprints together, the meetings are becoming ninety minutes or less in duration for a one week Sprint. My initial agenda is as follows: - Demonstrations where the Team shows the Product Owner the work they achieved and receives Story Point awards based on their accuracy.

- The Retrospective comes next, aided by a host of metrics that I track. I only track whole-team metrics, never individual metrics. Initially, though I publish many metrics, I only focus on Velocity, Burndown, Work Capacity and Commitment Accuracy.

- Product Backlog Presentation follows, during which the Product Owner discusses the content of the Backlog at that point in time. The Team is free to question motives, suggest alternatives and add requirements at this point. I reject any improperly formed User Stories on behalf of the team.

- Estimation and Negotiation signals that the meeting is nearly complete. They happen in a single motion with my new teams, though more mature teams eventually choose to split these activities into unique meetings. The Product Owner participates in an advisory role only during this phase of the meeting. I spend most of my time in this phase trying to keep the teams from unnecessarily breaking Story Cards down into task sequences, which some tend to do. The INVEST mnemonic is really handy here.

- Sprint Backlog Commitment is the final act of the Planning Meeting. In the first few Sprints, I literally read aloud what "Commit" does and does not mean so that there is no doubt in anyone's mind. Once the team commits to the work, the meeting adjourns.

- Multi-Tasking is Forbidden. Work must be in Priority Order.

Some Engineers understand this right away. Others feel most productive or fulfilled when they have multiple projects in progress and they don't appreciate my pointing out that there is no value in incomplete work – but point it out, I do. And often. I insist and enforce that they work on cards without multi-tasking and in priority order.

I also have standard layouts that I use for their initial Sprint Planning Boards, User Stories, Story Cards, Burndown Charts and Velocity tracking. I take full responsibility for entry and management of the (horrible) Scrum tool that we have at the moment so that they don't have that misery to deal with on top of learning everything else.

As I said in the beginning, I do try to get all of this done with a friendly smile and a "please" but generally have to insist -- sometimes quite forcefully -- to get all of them moving. Although the beginning is rocky, we usually start laughing and having fun in the meetings within a week. And as they become more compliant and competent with Scrum, I quickly relax my grip on some of the rules and let them redesign their environment to their own liking – so long as they continue to respect the principles of Scrum.

Three key reasons that I believe I am successful with this approach are:

- I find the biggest, nastiest problem that the team has and solve in within a day or two of the first Planning meeting. Some teams quickly volunteer this problem to me in their first Retrospective while others require observation, careful listening and behind-the-scenes reconnaissance to tease it out. Especially for those teams who haven't worked directly with me yet, having that very large problem go away underscores that they are important to me, that I take them seriously and that I am working hard to make their world a better place.

- Since I am the Master Scrum Master/Scrum Evangelist for the entire company, I am almost never their permanent Scrum Master for any given team. This gives me the freedom to create a bit (but only a very small amount) of "Us vs. Him" atmosphere at first. It causes the team to bond in an entirely new way than they have before, and also sets up their permanent Scrum Master to be the "good cop" down the road. It also allows me to be more firm about standing during Stand-Up, keeping your estimates private until the vote is called during estimation, etc. Keeping in mind that I generally have to bow out and move on to another team after 6-12 weeks, by which point they are functioning very well and are (on average) around the 500% mark, most teams tolerate this very well and learn good habits more quickly – even if it does leave me feeling a bit a schoolmarm.

- I think Socrates was on to something. When I see something going wrong – say, someone sitting during the Daily Stand-Up – I don't always address the transgressor directly. Instead, sometimes I stop the meeting and ask the team, "Team, do any of you see something going wrong with our meeting right now?" Ironically, it is almost always the most skeptical person who is the first to correct the insolently perched teammate. Soon, they start calling one another on leaning or sitting long before I stop the meeting and ask what's going wrong. It helps them begin to police themselves so that I don't always have to be around to elicit good behavior.

This is roughly how I have driven teams into hyper-productivity in as few as four weeks, and why one of my co-workers calls me "The Scrum Whisperer." I have one team that has achieved 1,650% higher targeted value contribution per week after just four months (16 Sprints) together. We are pretty proud of those numbers. I've also noticed that teams using this "quick format" approach tend to hit their Velocity elbow much sooner, giving Product Owners a greater and more stable view of the roadmap than teams who use longer Sprints or spend their inaugural period hashing out where they want their Scrum Board to be located.It's a fairly large culture shock for most teams and doesn't yield a lot of "let's go to lunch" invitations at first. But, per feedback from my VP of Engineering, "

They only hate [me] for about 2-3 weeks. Then they're indifferent to [me] for another few weeks. Then they scream bloody murder if [he tries] to take [me] away from them." I do stay in touch with teams that I've kick-started like this and, with one notable exception, they have all continued their trend of improvements in my absence.

I hope you'll find some of this helpful as you try to slingshot your teams into optimum Scrum performance. If I can be of further assistance, I would be happy to help. I'm also very interested to hear of your experiences, and your opinions of my techniques which are always evolving.

Best,

Scott Downey

http://www.MySpace.com/PracticalScrum

Scrum is an Agile development framework that Jeff Sutherland invented at Easel Corporation in 1993. Jeff worked with Ken Schwaber to formalize Scrum at

Scrum is an Agile development framework that Jeff Sutherland invented at Easel Corporation in 1993. Jeff worked with Ken Schwaber to formalize Scrum at